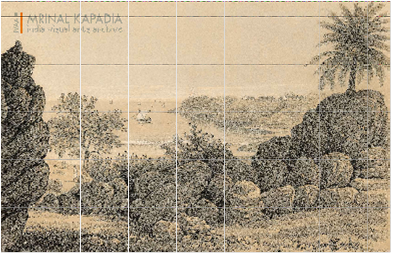

Looking from Chowpatty towards Malabar Point today, the southern tip of Malabar Hill, we still see vestiges of this view from over a century and a half ago, mostly thanks to the near-pristine 49-acre Raj Bhavan Complex estate, home to the Governor of Maharashtra. A microcosm of what was a thickly wooded forest, the estate houses several species of flora and fauna, including 9 resident peacocks, as well as a private beach!

Boasting the highest point on the erstwhile island city, Malabar Hill had always provided a good lookout point in the heyday of ship faring days. While there was very little local trade output in the Pre-Portuguese and Portuguese periods, Malabari pirates (from Kerala, after whom the hill was named) would wait atop the hill looking to intercept British ships sailing in and out of Bombay harbour in the early days of the English East India Company, who were struggling to maintain their upstart outpost as they tried to develop it into a port of significance.

Even though the primary legend associated with the hillock is that of the Banganga tank, built atop a fresh water spring of unknown source, something that would’ve seemed magical so close to the sea, a lesser-known but equally important one, related to a rite of passage for the purification of one’s past deeds (and future endeavours), was also present just a few hundred metres south of the tank. Both legends, incredibly, have origin stories related to Lord Rama.

Shri-Gundi, or “Lucky Stone”, was the original name of Malabar Point – a cleft rock on the slope of the southern extremity of the hill. Close to the water, it was hard to climb due to the incessantly surf-buffeted rocky promontory, and was particularly inaccessible during the stormy season. So one would descend some steps on rugged rocks from the land side, and thrusting their hands in front, ascend head-first up the hole. Numerous pilgrims, men and women, over generations and centuries, resorted to the rock for the purpose of regeneration by the efficacy of a passage through this sacred emblem. It is said that Shivaji, founder of the Maratha empire, jeopardized his liberty and life for the advantages of such a regeneration. As did Raghunath Rao, the father of the last Peshwa, who even sent two emissaries to Britain and had them perform the ritual on their return for having passed through, and lived in, debasing countries! The rock has since been lost to time.

A virtually inaccessible jungle, the winds of fortune swayed in favour (or perhaps quite the contrary?) of this spot in the 19th century, when after being used as a private home by Governor Montstuart Elphinstone in the 1820s, the lone former hunting lodge, seen here in the image next to the flagstaff at land’s end (Bishop Reginald Heber in the same decade described it as “a very pretty cottage in a beautiful situation on a rock and a woody promontory actually washed by the sea spray”), had by the 1880s become the permanent residence of the Governor of Bombay, which would eventually expand into the Raj Bhavan Complex we know today. The government complex in Parel was found to be polluted due to the influx of factories and the water insanitary, with Lady Ferguson (wife of the then-Governor) having died of cholera while her husband was in office. With this shift in base of power, Malabar Hill experienced a surge in population, starting with the Europeans and the Parsis, and eventually followed by members of other religions and communities, as it became fashionable to live here, apart from the obvious benefit of being close to favour.

I’ll leave you with one last description of a warning of what was thought might be lost in the name of development and progress, penned presciently in the late 19th century, and beyond evident for us to see today: “It is curious to note, on Malabar Hill, that what has become the latest and, in some respects, the most favourite abode of our citizens, appears to have been the very first site chosen by man on our island. There is such a thing as beauty and harmony of form; and if every man is permitted to erect anything he pleases, then we may bid adieu to the inheritance of beauty that has come down to us in Malabar Hill, blessed in the poetry of Nature, but deficient in the poetry of Art.”

(Picture and article by Mrinal Kapadia, resident of Cumballa Hill, he is a collector and researcher, and can be reached on mrinal.kapadia@gmail.com or via Instagram on @mrinal.kapadia)